'Detail, The Dawn of Peace' a painting of afterlife scenes in the Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Centre, Edinburgh

It is often claimed – a sound bite – that “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence”.

In fact, this is a philosophical statement masquerading as a scientific principle.

It’s not a recognised test in English or Scots law either – a judge never asks for ‘extraordinary evidence’!

There is no fixed legal test for what is ‘extraordinary’ since this varies with time and place. As was said by Lord Salmon in the context of evidence law fifty years ago: “What is striking in one age is normal in another: the perversions of yesterday may be the routine or the fashion of tomorrow” in Boardman v Director of Public Prosecutions [1974]. [1]

It has been a point echoed by psychical researchers, especially in the early 20th century with the life after death. Many things once deemed impossible in the 19th century had come true with advances in technology.

All the Court can do is determine a claim on what evidence is produced in the form of testimony before it and whether the threshold of the balance of probabilities or more likely than not (a civil case) or beyond reasonable doubt.

Naturally, in many fields in science, particularly with unusual medical and mental conditions, there are splits in opinion, for example the mental capacity of someone who has committed a crime. However, courts cannot determine the scientific validity of any scientific theory, they can only hear the current opinion of some facts so far as it may be relevant to any issue, and hear any contrary argument

This is even more true with subjective beliefs concerning religion and the afterlife and survival after death. Courts are not testing laboratories and have no way of verifying if claims are true except by way of examination of testimony and admissible evidence. If scientists can’t decide a matter, then the courts can hardly be expected to help them.

In March 1944, an Old Bailey jury famously turned down the opportunity for the medium Helen Duncan to test her powers in court when she was charged under the Witchcraft Act 1735 of falsely conjuring spirits on account of seances she had performed in Portsmouth. She offered to prove her powers were real before them but it was declined by both the judge and jury. This became an appeal point before the Court of Appeal, but it failed.

The Court of Appeal ruled what was at issue was whether Duncan cheated on another occasion and broken the law, at a particular séance held in January 1944, not whether she really had powers or could call up spirits generally. The jury found that she faked everything on that previous occasion. The Court of Appeal re-affirmed that a court room is not a testing laboratory.[2]

The case of Cummins v Bond [1927]

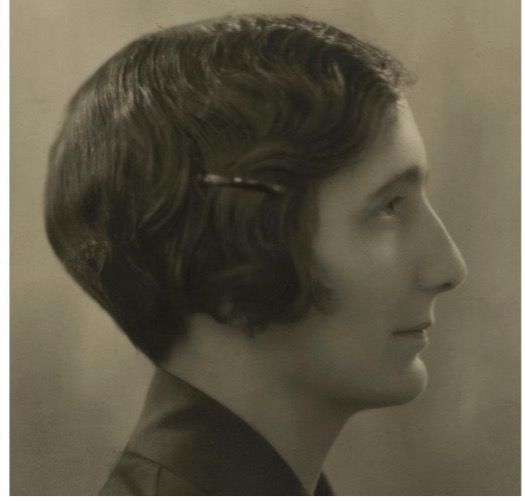

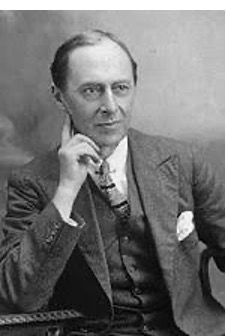

Geraldine Cummins and Frederick Bligh Bond

Another occasion when questions on the reality of spirits arose was a copyright dispute in 1926. This was the case of Cummins v Bond [1926] brought under the Copyright Act 1911 over scripts written in trance by medium Geraldine Cummins. [3]

She said the writings were dictated to her by a spirit identifying itself as Cleophas a character in the New Testament who had known Christ and who had allegedly had last been embodied in the flesh some 1900 years earlier. Geraldine’s hand held the pen and wrote whilst she was in an unconscious trance state.

Imaginative impressions of Cleophas by artists across the centuries

Frederick Bligh Bond (1864-1945) who arranged the seances and transcribed the messages afterwards believed he could claim copyright and sued Geraldine Cummins when she wanted to publish them herself. Both plaintiff and the claimant believed in spirits.

Though finding for her Mr Justice Eve refrained from formally acknowledging or accepting or rejecting her claim the spirit of Cleophas wrote everything through her.

Basically, she held the pen and was deemed to be the author. The court could not enquire further as to what was actually going on in her brain. She alone, not Frederick Bligh Blond was entitled to copyright.

The judge also rejected an alternative idea this was a case of telepathy. He said Bond was ‘labouring under a complete delusion in thinking that he in any way contributed to the production of these documents’ on the evidence.

It was a polished judgement which deftly avoided the key question of the survival of individual consciousness after death or telepathy. Altogether, Mr Justice Eve refused to make any finding as to spirits or that Cleophas was a joint author stating:

“…. I do not feel myself competent to make any declaration in his favour, and recognizing as I do that, I have no jurisdiction extending to the sphere in which he moves, I think I ought to confine myself when inquiring who is the author to individuals who were alive when the work first came into existence and to conditions which the legislature in 1911 may reasonably be presumed to have contemplated.” [4]

The situation remains the same nearly a century later.

However, there may be some claims of psychic phenomena where principles used in the law of evidence may be helpful in strengthening the credibility of claims of paranormal occurrences as will explored in in future postings….

[1] [1974] 3 All ER 887.

[2] R v Duncan and Others - [1944] 2 All ER 220

[3] Cummins v Bond [1927] 1 Ch. 167

[4] Cummins v Bond [1927] 1 Ch. 167 at page 175.