Elliot O’Donnell, the Master Ghost Hunter: his stories may be fantasy but why have they not been dramatised?

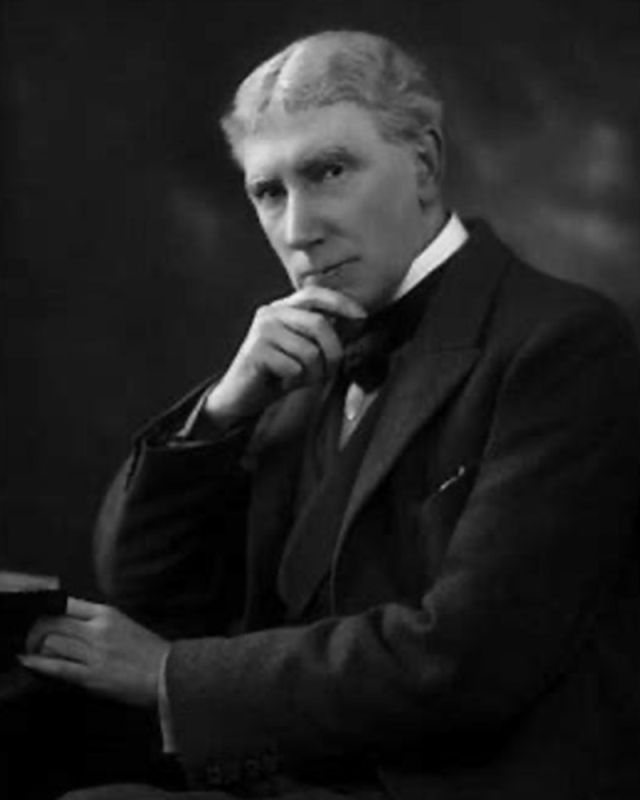

Though it may be nearly 60 years since he became a ghost himself the name of ghost hunter Elliot O’Donnell, ‘master ghost hunter’ lives on.

For over sixty between the 1890s and the 1950s O’Donnell presented himself as the most active of Britain’s ghost hunters with a wealth of stories. A prolific author, to an extent he both created and then dominated the market in ‘true’ ghost stories in the early 20th century, producing dozens of volumes featuring the most extraordinary and alarming accounts of hauntings. He claimed personal experience of many of them.

His books include (this no means an exhaustive list) include: Ghosts of London, Some Haunted Places in England, Byways of Ghostland, Some Ghost Stories, Twenty Years Experience As A Ghost Hunter, Haunted Churches, Some Haunted Houses of England and Wales, Haunted Britain, Ghostly Phenomena, The Banshee, Werewolves etc. Certain themes and sub-categories inspired full length books Ghostly Animals, Family Ghosts, Dangerous Ghosts, Haunted Waters, Trees of Ghostly Dread published between 1908 – 1958. He also wrote on crime and unsolved mysteries.

O’Donnell usually worked alone as a ghost hunter, relying upon his own eyes a self-proclaimed inherited psychic faculty rather than gadgetry (much in the way of film and sound recording equipment was in its infancy). His stories often involve his sitting up alone late at night in haunted houses, either with a candle, or later a torch, promptly extinguished once manifestations commence. A loner in research terms, he distinguishes and distancing himself from psychical researchers who might adopt a more scientific paradigm (though at the end of Haunted Britain (1948) he says he did once met Frederic Myers (1847-1901) a founder of the Society for Psychical Research). He sometimes accompanied newspaper reporters on ghost hunts or other local people, but his works lack independent corroboration.

The resultant books are all radically different to the sober accounts of those involved in serious scientific research as is apparent if you compare the sober scientific tone of Professor Hornell Hart’s ‘Six Theories on Apparitions’ published in 1956 with one of Elliot O’Donnell’s last compilations Trees of Ghostly Dread (1958) you will find it hard to believe they were published in the same century let alone just two years apart.

In depth analysis of experiences is lacking since; O’Donnell never lingers before breathlessly moving to the next one, seeing ghosts as active presences, here and now. Alas, quantity does not equate to quality. Even as ghost books, they don’t count in any way as serious contribution to paranormal literature because of the fragrant embroidery, exaggerations and down-right inventions. They provide thrills of the penny-dreadful variety, but not much more. Nonetheless, their impact on impressionable children and adolescents can be considerable. Probably with some adults as well, to the point they still can resonate with a small minority of readers today. I first started reading his stories in my early teens, and for many seriously interested in reading about the paranormal his hair-raising tales may qualify a guilty pleasure dreamed up in a very different era.

Aside from his own hair-raising personal accounts, O’Donnell’s books add thinly disguised retellings of old stories, peppered with some more plausible and independent reports and examples of sheer invention presented as fact.

O’Donnell tells readers ghosts do not come to order, nor does he order or weigh up the veracity of his stories in any coherent way in his book, other than classifying them into the broadest of categories. He tells of seeing his first apparition, a strange spotted entity aged five and later of being nearly strangled by a ghost. At Pitlochry in Scotland, he was lucky to escape the grasp of a white figure at a cross-roads, since its touch could prove fatal. Many similar sightings and adventures follow, representing an amazing success rate if true. One soon loses count…

However, anyone seeking actual confirmation of their veracity or and details will be wholly frustrated by a lack of sources, identities or even any indications as to the decade when many of these alleged ghostly encounters supposedly occurred.

True, O’Donnell’s works contain a smattering of contemporary reports, and a number of personal eye-witness reports culled from newspapers from the 1880s to the 1930s but that’s scarcely saying much. He also rescued from obscurity fragments of traditional lore in footnotes gleaned from obscure local historical works and cites newspaper stories between the 1880s to the 1930s. Altogether, it is easy to dismiss them as random assemblies with nuggets buried like silver coins in a Christmas pudding; but that could be said of many other ghost books.

This output of material did not stop with O’Donnell’s death, as shortly before he left this Earth, the task of anthologising his work was taken up by writer Harry Ludlam who had produced a biography on Bram Stoker the author of Dracula in 1962. The first was The Screaming Skull and Other Ghost Stories (1964), containing thirty eight of O'Donnell's tales arranged by Ludlam and followed by a second posthumous volume, The Midnight Hearse and More Ghosts (1965), containing another thirty seven tales. Ludlam also tried his hand at a compilation of true ghosts The Restless Ghosts of Ladye Place and other true hauntings (1968) (somewhat better on sources than O’Donnell). Later Ludlam proved curiously reticent about his role keeping O’Donnell in print and when invited to address the Ghost Club in 2008 he declined saying it was all a longtime ago.

Altogether might be fairest to say that Elliot O’Donnell wrote both a little bit of fact and an awful lot of imaginative fiction. Because of this his books cannot rate in any way as either evidence of contemporary ghost beliefs or experiences or help in the assessment of spontaneous case reports today in psychical research (O’Donnell was a member of the Society for Psychical Research for two short periods with nearly a fifth year interval between them, the first in 1899-1900 and then for one year in 1948 when he brought out his book Haunted Britain At most they can be used as a means of sharpening the sceptical nose any aspiring serious investigator.

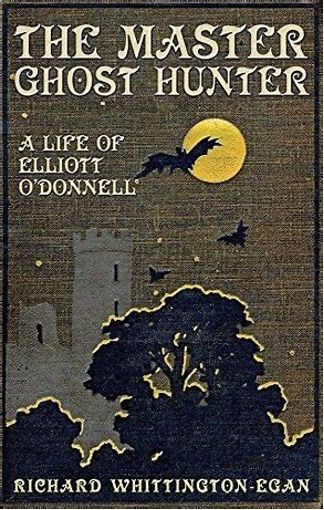

It is surprising that some of them haven’t been filmed, given the enormous volume of them he published (for a list of his books see the late Richard Whittington Egan’s The Master Ghost Hunter: A Life of Elliot O’Donnell (2016).

M.R. James (1862-1936) believed in ghosts but hoped O’Donnell’s stories weren’t true.

Whilst ghost stories of M.R. James remain in print, have been frequently anthologised and have undergone many adaptations and dramatizations over the years, O’Donnell’s books been ignored by the modern entertainment industry. Wondering why this is so perhaps goes to the difference that James assured readers were fiction. In contrast, O’Donnell averred his chilling ghost stories were true!

Indeed, James references Elliot O’Donnell’s in an essay published in 1927, ‘Some Remarks on Ghost Stories’. James saw as ‘the true aim of the ghost story’ being ‘a story written with the sole object of inspiring a pleasing terror in the reader’. This is what a fictional story does, with the reader feeling safe and comfortable at the end knowing it is only a story and perceptions of the normal world need not be changed. In contrast, O’Donnell claims his ghosts are factual hinting the universe is not the predictable or ordered place we imagine. James commented:

Mr Elliott O’Donnell’s multitudinous volumes I do not know whether to class as narratives of fact or exercises in fiction. I hope they may be of the latter sort, for life in a world managed by his gods and infested by his demons seems a risky business.

And that element ultimately has an unsettling effect on a psychological level, even if subliminally.

Perhaps C.S. Lewis got near the truth in his book Miracles (1948) when writing of legends in which beasts turn into men and men into beasts or trees and declared, ‘Some people can’t stand these stories, but others find them rather fun. But the slightest suspicion it was true would turn the fun into a nightmare.’

Nightmare is right. For the climate of O’Donnell’s ghosts are scarcely even 19th century, or even 18th century. One might even debate if they qualify as medieval in character for he presents a spirit world remote from any Christian depiction of the afterlife with its hopes of repentance, and final rest and salvation. Equally, his phantoms are distant from the comforting afterlife vision and claims of spiritualists where the dead can still converse lovingly with the living (O’Donnell denounced spiritualism in a book The Menace of Spiritualism (1920) though he later softened his viewpoint). Many of his ghosts are monstrous in appearance – from a Freudian context you might see certain examples of O’Donnell’s spectres as the id-personified. If anything, the worldview and atmosphere conjured up by O’Donnell is more in keeping with that revealed in ancient Babylonian texts, though correspondingly lacking any of their elaborate spells for protection, banishment and exorcism which scholars have laboriously transcribed.

In cinematic terms his ghosts on occasion can prove more extreme than the imagined phantoms in such film classics as The Haunting (1963) and The Legend of Hell House (1973) and, in the most extreme stories, his phantoms are only a few steps away from the ghastly possessing entities in the notorious ‘video nasty’ The Evil Dead (1982). However, in O’Donnell the ghosts usually just scare, threaten and menace, save where they inspire the living to commit actual crimes and murders.

The obscurity of his stories for many of a social-media generation may be an issue, or that readers come away to overwhelmed to think of delving into them again. Maybe copyright is an issue; a fact to be checked.

Or perhaps O’Donnell’s work is seen as uncomfortable because he refused to yield to the fashions and pressures of either the literary ghost story or contemporary ghost belief; he gives the impression of a spectre-stricken world where terrifying phantoms can be readily encountered. Much of O’Donnell’s output, the majority of it, could be explained away, but there may just be a lingering doubt that on a deeper level which some imaginative and creative people find frightening, ‘the slightest suspicion’ it was true?